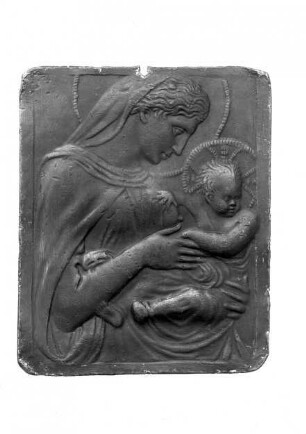

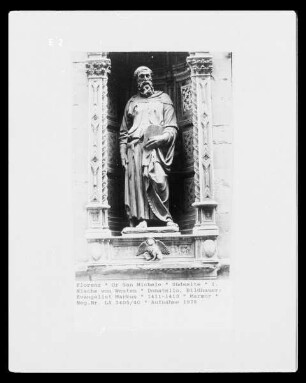

Relief

Madonna mit vier Cherubim / Virgin and Child with four Cherubs

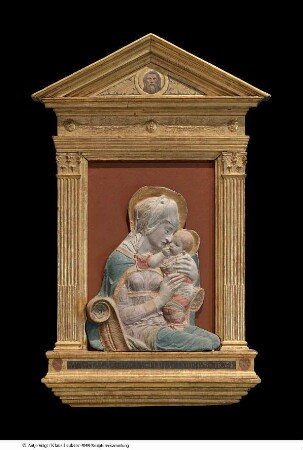

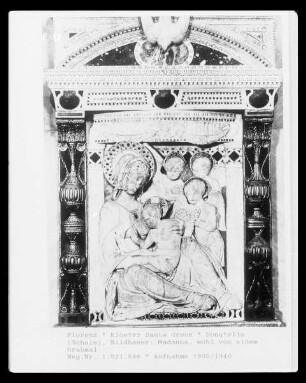

Dieses Relief veranschaulicht, wie Donatello mit instabilem Gleichgewicht gespielt hat: Die Jungfrau hält ihre Hände nicht nur zum Beten, sondern sie hält auch ihr Kind unter dem Arm. Jesus versucht, in seiner Haltung zu bleiben und segnet gleichzeitig den Betrachter mit seiner rechten Hand. Durch diese Gleichzeitigkeit dieser Bewegungen wird der Betrachter Teil der heiligen Szene. Vor 1945 war das Werk mit üppigen Farben geschmückt. Erworben 1888 This relief shows nicely how Donatello liked to play with unstable equilibrium: the Virgin is not only praying with her hands, but also holding her baby under her arm. Jesus tries to maintain his stance but is also blessing the beholder with his right hand. Thanks to these simultaneous actions, the viewer is engaged in the sacred scene. Before 1945, the work was adorned with lavish colors. Donatello Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi Florence ca. 1386-1466 Virgin and Child with four Cherubs ca. 1440-50 Terracotta with traces of color 102 x 72 cm Frame bearing the Rucellai family coat of arms lost since 1945; not original with the relief. Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Skulpturensammlung, Inv. SKS 54. Bode-Museum, on view. Provenance Florence, Santa Maria Maddalena dei Pazzi (until ca. 1888); Florence, Stefano Bardini (1888); Berlin, Skulpturensammlung/Altes Museum (1888-1904); Berlin, Skulpturensammlung/Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum (1904-1939); Berlin, storage (1939-1945); Soviet Union, secret storage (1945/46-1958); East Berlin, Skulpturensammlung/Bode-Museum (1958-1990); Berlin, Skulpturensammlung/Bode-Museum (1990-present). Acquisition Bought in 1888 from the Florentine dealer Stefano Bardini for 43,000 Italian lire. The acquisition file of the Berlin Museum (2353/88) is missing from the Zentralarchiv der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin. Restorations 1958; 1977. Exhibitions Schätze der Weltkultur von der Sowjetunion gerettet, East Berlin, Nationalgalerie and Pergamonmuseum, 1958, cat. D 48. Das verschwundene Museum. Die Berliner Skulpturen- und Gemäldesammlungen 70 Jahre nach Kriegsende, Berlin, Bode-Museum, 19 March-27 September 2015. Bibliography Bode 1894 Wilhelm Bode, Denkmäler der Renaissance-Sculptur Toscanas, Munich, F. Bruckmann, 1894, II, pl. 100: Donatello. Bode 1902 Wilhelm Bode, Florentiner Bildhauer der Renaissance, Berlin, Bruno Cassirer, 1902, p. 109 fig. 42, p. 111. Balcarres 1903 Lord Balcarres, Donatello, London and New York, Duckworth & Co. and Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1903, p. 185: typical of Donatello, but the color is not original; comes from Santa Maria Maddalena dei Pazzi, Florence. Meyer 1903 Alfred Gotthold Meyer, Donatello, Bielefeld and Leipzig, Delhagen and Klafing, 1903, pp. 62, 116. Schottmüller 1904 Frida Schottmüller, Donatello. Ein Beitrag zum Verständnis seiner künstlerischen Tat, Munich, F. Bruckmann, 1904, pp. 75, 106-108, 129. Fabriczy 1906 C. de Fabriczy, “Memorie sulla chiesa di S. Maria Maddalena de’ Pazzi a Firenze e sulla Badia di S. Salvatore a Settimo”, L’Arte, IX, 1906, p. 262 note 27: the work was on the main altar of Santa Maria Maddalena dei Pazzi, Florence; sold by Bardini to the Berlin Museums together with a St Elizabeth by Rossellino (see Inv. SKS 1575). Schubring 1906 Paul Schubring, Donatello. Des Meisters Werke in 277 Abbildungen, Stuttgart and Leipzig, Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1907, pp. 128, 200: Donatello. Sirén 1909 Osvald Sirén, Florentinsk Renässansskultur och andra Konsthistoriska ämnen, Stockholm, Wahlström & Widstrand, 1909, p. 62. Bertaux 1910 Émile Bertaux, Donatello, Paris, Plon, 1910, p. 159, pl. XVII: the best relief by Donatello during the Paduan period. Cruttwell 1911 Maud Cruttwell, Donatello, London, Methuen, 1911, p. 136: not by Donatello, probably derived from an original. Schottmüller 1913 Frida Schottmüller, Die italienischen und spanischen Bildwerke der Renaissance und des Barocks in Marmor, Ton, Holz und Stuck, Berlin, Georg Reimer, 1913, p. 19 cat. 38: Donatello, just before the Paduan period; the upper left cherub is related to the choir tribune of Padua; the frame with the Rucellai coat of arms dates ca. 1475. Bode 1921 Wilhelm Bode, Florentiner Bildhauer der Renaissance, Berlin, Bruno Cassirer, 1921, p. 103 fig. 58: workshop of Donatello. Bode 1922 Wilhelm Bode, Die Italienische Plastik, 7th ed., Berlin and Leipzig, Vereinigung wissenschaftlicher Verleger and De Gruyter, 1922, p. 73, fig. 35: Donatello. Wulff 1922 Oskar Wulff, Donatello, Leipzig, E. A. Seemann, 1922, pp. 14-15, fig. 35. Bode 1923 Wilhelm von Bode, Die Kunst der Frühenrenaissance in Italien, Berlin, Propylaën-Verlag, 1923, pl. IV: Donatello, color reproduction. Knapp 1923 Friedrich Knapp, Die Italienische Plastik von XV. bis XVIII. Jahrhundert, Munich, Hyperion, 1923 (2nd edition), p. 26, pl. 34. Schottmüller 1932-33 Frida Schottmüller, “Ein Jugendwerk Donatellos im Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum”, Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, I, 1932-33, p. 340. Schottmüller 1933 Frida Schottmüller, Die italienischen und spanischen Bildwerke der Renaissance und des Barock. Erster Band. Die Bildwerke in Stein, Holz, Ton und Wachs, Zweite Auflage, Berlin and Leipzig, Walter de Gruyter & Co., 1933, pp. 7-8: Donatello, just before the stay in Padua; said to come from Santa Maria Maddalena dei Pazzi, Florence. Bange 1934 E. F. Bange, Die Italienischen Bildwerke im Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum, Berlin, Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, 1934, p. 22: Donatello, just before the Paduan period. Kauffmann 1935 Hans Kauffmann, Donatello. Eine Einführung in sein Bilden und Denken, Berlin, Grotesche Verlagsbuchandlung, 1935, p. 83, 93, 122, 156, 223 note 257: Donatello; in stucco. Goldscheider 1947 L. Goldscheider, Donatello, Paris, Phaidon, 1947, p. 38 fig. 105, p. 39: Donatello. Galassi 1949 Giuseppe Galassi, La scultura fiorentina del Quattrocento, Milan, Ulrico Hoepli, 1949, p. 104: Donatello, ca. 1440. Paatz 1952 Walter and Elisabeth Paatz, Die Kirchen von Florenz. Ein kunstgeschichtliches Handbuch, IV, Frankfurt am Main, Vittorio Klostermann, 1952, pp. 103, 119 note 100: Donatello, ca. 1435, stucco; comes from the area of the choir of Santa Maria Maddalena dei Pazzi. Verzeichnis… 1953 “Verzeichnis der im Flakturm Friedrichshain verlorengangenen Bildwerke der Skulpturen-Abteilung”, Berliner Museen, new series, III, n° 1-2, 1953, p. 11: burnt between 5 and 10 May 1945. Clark 1958 Kenneth Clark, “Donatello”, Apollo, LXVIII, July-December 1958, p. 227: surprising that the work is not included in the monograph on Donatello published by H.W. Janson in 1957; “the execution may be questioned but the invention is magnificent”. Grassi 1958 Luigi Grassi (ed.), Tutta la scultura di Donatello, Milan, Rizzoli, 1958, p. 101: late follower of Donatello; destroyed in 1945. Pope-Hennessy 1958 John Pope-Hennessy, Italian Renaissance Sculpture, London, Phaidon Press, 1958, p. 23 and fig. 28: Donatello, formerly in Berlin. Schätze der Weltkultur… 1958 Schätze der Weltkultur von der Sowjetunion gerettet, exh. cat. (East Berlin, National-Galerie and Pergamonmuseum, 1958), East Berlin, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 1958, cat. D 48: Donatello. Grohn 1959 Hans Werner Grohn, “Report on the Return of Works of Art from the Soviet Union to Germany”, The Burlington Magazine, CI, n°670, January 1959, p. 61: the relief was “shattered in fourteenth pieces” in 1945; “It must be stressed that in no case were there any additions made in the process of restoration, but permanent losses of material were substituted by some neutral ingredient”. Malerei und Plastik… 1960 Malerei und Plastik. Meisterwerke aus acht Jahrhunderten, East Berlin, Henschelverlag, 1960, pp. 106-107. Fründt 1963 Edith Fründt, Italienische Plastik des 15.-17. Jahrhunderts, East Berlin, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 1963, p. 12 cat. 4. Pope-Hennessy 1966, ed. 1968 John Pope-Hennessy, “The Fifth Centenary of Donatello” 1966, in idem, Essays on Italian Sculpture, London and New York, Phaidon, 1968, p. 30: Donatello. Pope-Hennessy 1970, ed. 1980 John Pope-Hennessy, “The Altman Madonna by Antonio Rossellino”, Metropolitan Museum Journal, 1970 now in: idem, The Study and Criticism of Italian Sculpture, New York and Princeton, The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Princeton University Press, 1980, p. 143. Pope-Hennessy 1971 John Pope-Hennessy, Italian Renaissance Sculpture, London and New York, Phaidon Press, 1971 (2nd ed.), p. 20 and fig. 33: Donatello, much damaged. Pope-Hennessy 1976, ed. 1980 John Pope-Hennessy, “The Madonna Reliefs of Donatello”, Apollo, CIII, n° 169, March 1976 now in: idem, The Study and Criticism of Italian Sculpture, New York and Princeton, The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Princeton University Press, 1980, pp. 80-82: Donatello, beginning of the Paduan period; p. 82: “As a work of art the relief has been destroyed. It was one of the most beautiful Madonnas of the quattrocento, but nobody would guess that now. Nonetheless the pieces of it that are genuine still have some interest, simply because they prove that the relief was autograph. And none more so than the almost intact head of the Child”. McNeal Caplow 1977 Harriet McNeal Caplow, Michelozzo, New York and London, Garland Publishing, 1977, I, pp. 487-488, II fig. 188: attributed to Michelozzo, but perhaps modeled in another workshop. Knuth 1982 Michael Knuth, Skulpturen der italienischen Frührenaissance, East Berlin, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 1982, pp. 9-13: Donatello, ca. 1440. Pope-Hennessy 1983 John Pope-Hennessy, “A Terracotta ‘Madonna’ by Donatello”, The Burlington Magazine, CXXV, n° 959, February 1983, p. 84, fig. 25: compared to a Virgin and Child in the Cryan collection, Boca Raton. Bennett and Wilkins 1984 Bonnie A. Bennett and David G. Wilkins, Donatello, Oxford, Phaidon, 1984, p. 127. I. F. 1984 I. F., “New York. Terrakotta-Relief wird Donatello zugeschrieben”, Weltkunst, n°4, LIV, n°4, 15 February 1984, p. 277: related to the Virgin and Child from the Cryan Collection in Boca Raton, which is for sale. Sachs 1984 Hannelore Sachs, Donatello, East Berlin, Henschelverlag, 1984, chap. 6. Darr 1985 Alan Phipps Darr in Italian Renaissance Sculpture in the Time of Donatello, exh. cat. (Detroit, The Detroit Institute of Arts, 23 October 1985-5 January 1986), Detroit, The Detroit Institute of Arts, 1985, p. 114: compared to the Virgin and Child formerly in the Cryan Collection, Boca Raton. Gentilini 1985 Giancarlo Gentilini in Paola Barocchi et al. (eds.), Omaggio a Donatello. 1386-1986. Donatello e la storia del Museo, exh. cat. (Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, 19 December 1985-30 May 1986), Florence, SPES, 1985, pp. 267, 270 note 20: Donatello, before 1443 (because of its Florentine provenance). Avery 1986 Charles Avery, “Donatello’s Madonna Reconsidered”, Apollo, CXXIV, n° 295, September 1986, pp. 180-181: the motive of the praying hands of the Madonna may have been created by Donatello in Florence during the 1430s. Darr 1986 Alan Phipps Darr in idem and Giorgio Bonsanti (eds.), Donatello e i suoi, exh. cat. (Florence, Forte del Belvedere, 15 June-7 September 1986), Detroit and Florence, The Detroit Institute of Arts, La Casa Usher and Arnaldo Mondadori Editore, 1986, p. 151. Avery 1988 Charles Avery, Studies in European Sculpture II, London, Christie’s, 1988, p. 12 fig. 18. Avery 1989 Charles Avery, “Donatello’s Madonnas Revisited”, in Donatello-Studien, Munich, Bruckmann, 1989, pp. 221-221, 228, 232. European Works of Art and Sculpture 1990 European Works of Art and Sculpture, London, Sotheby’s, 13 December 1990, p. 24 lot. 34: compared to a Virgin and Child for sale as “circle of Donatello” now in Fort Worth, Kimbell Museum of Art. Avery 1991 Charles Avery, Donatello. Catalogo completo delle opere, Florence, Cantini, 1991, pp. 16, 91 cat. 54: the provenance from Santa Maria Maddalena dei Pazzi is related to the works made by Donatello for the Pazzi family. Pope-Hennessy 1993 John Pope-Hennessy, Donatello Sculptor, New York, London and Paris, Abbeville Press, 1993, pp. 261-262: Donatello, made in Padua ca. 1447 as the Child is similar to the one for the High Altar of the church of Sant’Antonio, Padua; no followings of this work in Florence but prefigures the painted Madonnas by Andrea Mantegna; p. 344 note 21: one of the greatest of Donatello’s reliefs; head of the Virgin close to the one of the High Altar, Padua; and the hands similar to the ones of St Justine in the same work. Rosenauer 1993 Artur Rosenauer, Donatello, Milan, Electa, 1993, pp. 246, 305 cat. 74: Donatello, ca. 1450. Directly compared to the Miracle of the Mule made for the High Altar of the church of Sant’Antonio, Padua. Pope-Hennessy 1996 John Pope-Hennessy, An Introduction to Italian Sculpture. Volume II. Italian Renaissance Sculpture, London, Phaidon, 4th edition, 1996, pp. 66, 70, 355: Donatello, ca. 1450. Bellosi and Gentilini 1996, ed. 1998 Luciano Bellosi and Giancarlo Gentilini, “Una nuova Madonna in terracotta del giovane Donatello”, Pantheon, LIV, 1996, pp. 19-26 (reprinted as a volume: Una nuova Madonna in terracotta del giovane Donatello, exh. cat. Turin, Antichi Maestri Pittori, 4 April-30 May 1998, Turin, Antichi Maestri Pittori, 1998), p. 10. Jolly 1998 Anna Jolly, Madonna by Donatello and his Circle, Frankfurt am Main et al., Peter Lang, 1998, p. 114 cat. 22.1: Donatello, c. 1440s. Called the “Bode Madonna”; composition close to the Altman Madonna in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Inv. 14.40.680); p. 121: compared to the Verona Madonna type (see Inv. SKS M 24; Inv. SKS M 268). Piccininni 1999 Francesca Picininni in Sulle tracce di Donatello: l’altarolo quattrocentesco del Museo Civico d’Arte, cat. exh. (Modena, Museo Civico d’Arte, 4 December 1999-May 2000), Modena, Comune di Modena, s. d. 1999, p. 8: compares the frame lost in 1945 with the one of the Cavalcanti Annunciation by Donatello in Santa Croce, Florence; p. 12. K,uth 2006 Michaël Knuth in Skulpturensammlung im Bode-Museum, Munich et al., Prestel, 2006, pp. 126-127. Lambacher 2006 Lothar Lambacher (ed.), Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Dokumentation der Verluste. Skulpturensammlung. Band VII. Skulpturen. Möbel, Berlin, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin-Preußischer Kulturbesitz, 2006, p. 227: the frame was kept on Museum Island during WWII, but is not recorded in a crate; it has been lost since 1945. Bormand 2007 Marc Bormand, “Desiderio: Style Aspiring to Grace”, in idem, Beatrice Paolozzi Strozzi and Nicholas Penny (eds.), Desiderio da Settignano. Sculptor of Renaissance Florence, exh. cat. (Paris, Musée du Louvre, 27 October 2006-22 January 2007; Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, 22 February 2007-3 June 2007; Washington, National Gallery of Art, 1 July 2007-8 October 2007), Paris and Milan, Musée du Louvre and 5 Continents, 2007, p. 53: the cherubs prefigure the ones of Desiderio da Settignano in his Foulc Madonna in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Bormand 2008 Marc Bormand, Donatello. La Vierge et l’Enfant. Deux reliefs en terre cuite, Paris, Musée du Louvre and Somogy, 2008, pp. 14, 22 note 37, p. 46 fig. 22: compared to the Virgin and Child in the Musée du Louvre (Inv. RF 353); and to the so-called San Felice Madonna (once in the Cryan Collection, Boca Raton). Reproduced in color after an indication by Michaël Knuth. Important Old Master Paintings and Sculpture 2008 Important Old Master Paintings and Sculpture, New York, Sotheby’s, 24 January 2008, pp. 206-208: related to the Louvre and formerly Cryan Madonnas. Knuth 2008 Michael Knuth, “Die Lösung stand im Bücherregal”, Sculptura. European Sculpture Fair, fair catalogue (Berlin, Deutsches Historisches Museum, 12-16 November 2008), Berlin, 2008, pp. 10-11: republishes the color photograph of the work that was printed in Bode 1923 but remained unnoticed; another photo shows the work in pieces in Soviet Union between 1946 and 1958. Bormand 2012 Marc Bormand, “Autour de quelques exemples de reliefs de Donatello sur le theme de la Vierge et l’Enfant”, Technè, 36, 2012, p. 45. Sbaraglio 2012 Lorenzo Sbaraglio, “Una terracotta di Donatello: la Madonna della tomba di Giuliano Davanzati in Santa Trinita”, Nuovi Studi, XVII, n° 18, 2012, pp. 45, 49. Chapuis and Kemperdick 2015 Julien Chapuis and Stephan Kemperdick (eds.), The Lost Museum. The Berlin Painting and Sculpture Collections 70 Years after Wold War II, exh. cat. (Berlin, Bode-Museum, 19 March-27 September 2015), Berlin and Petersberg, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin and Michael Imhof Verlag, 2015, pp. 114, 120-121: on the damages of WWII on the relief. Rowley 2015 Neville Rowley, “À la recherche des Donatello perdus, de Florence à Berlin”, Figura, 2015: http://figura.art.br/revista/studi-vari/studi-vari-3/4-a-la-recherche-des-donatello-perdus-de-florence-a-berlin: about the different impressions in front of the work in its actual state and looking at the pre-WWII color photograph. Comment The Virgin is praying while holding her son within her left arm; Jesus, dressed in swaddling clothes, stands on the lower edge of the relief, keeps his equilibrium with his left arm and blesses the beholder with the right one. Four cherubs are framing the upper part of the composition. The work was once highly praised for its painted and gilded decoration; Bode 1923 published a rare color photograph of it, which remained unnoticed in the literature until Knuth 2008 (Balcarres 1903 was the only scholar to question the authenticity of the painted decoration). In May 1945, the Madonna was caught in the fires in the Flakbunker Friedrichshain in Berlin; the relief was broken into many pieces and only a few traces of polychromy have survived. Even if the present condition of the Madonna with four Cherubs is problematic, there is no doubt that it is a masterpiece by Donatello (an attribution that has only been unconvingcingly challenged by Cruttwell 1911; and Janson 1957). The vivid and characteristic modeling of the artist is even more visible now that the painted decoration is gone, especially in the swaddling clothes of Christ (the photograph of the destroyed work, published by Kunth 2008, helps to distinguish the intact parts, directly modeled by Donatello – such as the body of the Child, his head and the arms of the Virgin – to the one that were recreated in 1958 – such as the lower part of her face. The overall composition can be understood as a brilliant idea of the master: the Virgin is praying and holding her Child at the same time with her left arm; the unstable position of Jesus and his gestures confer movement to the whole work. The center of the composition is occupied by the four hands of the Mother and Child, so naturally grouped that the symbolic meaning, although certainly intended, seems almost secondary. The four cherubs framing the central group all have different postures; as in many works by Donatello, almost every square inch of the relief seems to have been used to amaze the viewer. The work has been repeatedly compared to another Virgin and Child by Donatello now in the Musée du Louvre in Paris (Inv. RF 353; see Bormand 2008, both sculptures were sold through the Florentine dealer Stefano Bardini). Besides the treatment of color, the similarities between the two works are striking – hence implying a dating in the same years. Recent analysis has demonstrated that the clay used for the Louvre Madonna was likely to come from Northern Italy (see Bormand 2012), implying that the work was probably modeled during the stay of Donatello in Padua, between 1443 and 1454; incidentally, the gesture of the blessing Christ in the Louvre Madonna is also visible in the High Altar of the church of Sant’Antonio, Padua. This may also be the case of the Berlin relief, in which the same gesture is visible; the cherubs have also been compared with the one decorating the High Altar of Sant’Antonio (Schottmüller 1913). However, the fact that the work was in the Florentine church of Santa Maria Maddalena dei Pazzi until the late 19th century, as well as its similarities with another Virgin and Child apparently coming from Florence (formerly in the Cryan Collection, Boca Raton; similar to an autograph relief recently discovered in the Florentine church of Santa Trinita, for which see Sbaraglio 2012) cannot rule out a Florentine provenance. The work may have been made by Donatello during his decade spent in Padua, but in his native Florence, where he is documented several times. Before WWII, the relief had a frame decorated with the Rucellai coat of arms that was dated to ca. 1475 by Schottmüller 1913; it was lost during the war (Lambacher 2006). Picininni 1999 considered the frame original with the sculpture. However, an unpublished photograph of the relief in the Bardini archive, Florence, shows the work with another, probably 17th-century frame. Even though the documentation is lacking, this photograph suggests that the work may have been integrated in the baroque decoration of the choir of Santa Maria Maddalena dei Pazzi in Florence. Neville Rowley (15 February 2016)

- Standort

-

Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

- Sammlung

-

Skulpturensammlung (SKS)

- Inventarnummer

-

54

- Maße

-

Gewicht: insgesamt 110 kg (inkl. Halterung)

Höhe x Breite x Tiefe: 99,6 x 69,5 x 20 cm (Relief)

Tiefe: 9 cm Gestell

Tiefe: 20,5 cm Höchster Punkt mit Gestell

Gewicht: 91 kg

- Material/Technik

-

gebrannter Ton, mit geringen Fassungsresten

- Klassifikation

-

Relief (Sachgruppe)

- Bezug (was)

-

Madonna; d.h. Maria mit dem Christuskind

- Rechteinformation

-

Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

- Letzte Aktualisierung

- 09.04.2025, 10:14 MESZ

Datenpartner

Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst. Bei Fragen zum Objekt wenden Sie sich bitte an den Datenpartner.

Objekttyp

- Relief