Skulptur (visuelles Werk)

Madonna in der Nische / Virgin and Child

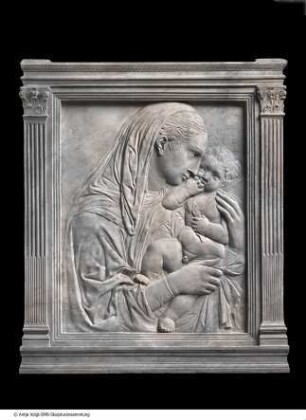

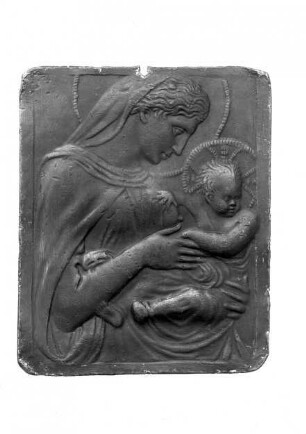

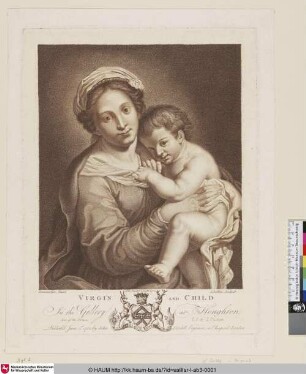

Attributed to Giovanni da Pisa – after Donatello? Giovanni di Francesco da Pisa, active in Padua in 1447-1448; died in Venice, shortly before 1460. Virgin and Child ca. 1450-55 Terracotta 75 x 54.5 cm Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Skulpturensammlung, Inv. SKS 2949. Bode-Museum, on view. Provenance Berlin, Adolph von Beckerath (until 1902); Berlin, Skulpturensammlung/Altes Museum (1902-1904); Berlin, Skulpturensammlung/Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum (1904-1939); Berlin, storage (1939-1945); Merkers, storage (1945); Wiesbaden, Central Collecting Point (1945-1956); West Berlin, Skulpturensammlung/Museum Dahlem (1956-1990); Berlin, Skulpturensammlung/Museum Dahlem (1990-1997); Berlin, storage (1997-2006); Berlin, Skulpturensammlung/Bode-Museum (since 2006). Acquisition Bought from Adolph von Beckerath in 1902 (acquisition file n°S479/02, untraced). Curatorial Files in the Bode-Museum Undated thermoluminescence, indicating the period 1450-78. Other versions • Vienna, Liechtenstein Museum, Inv. SK 133. Terracotta, 70 x 52 cm (without frame); 95 x 79.5 cm (with frame). Provenance: Stefano Bardini Florence (1900). No cushion on the edge. Modern frame. • Detroit, Institute of Arts, Inv. 31.37. Terracotta, 76.8 x 54.3 cm. Acquired in 1937. • Whereabouts unknown. Fragmentary, painted stucco. Negative 1538 BR of the Bardini archive in the Florence municipality (see Caglioti 2008, p. 90). Comment This relief in terracotta, especially refined, represents the Virgin and Child in an intimate embrace, the mother gently carrying her son while he holds her neck to kiss her cheek. The figures emerge from a sophisticated architectural setting, a niche seen in perspective decorated with two beautiful vases filled with ears of wheat, and two garlands attached at the top. On the buttresses flanking the niche stand pairs of musician putti. Many aspects of the work have been connected with the art of Donatello: the tenderness between the Virgin and Child (even the reaching gesture of the latter), the dynamic draperies of the Virgin, the classic yet inventive architecture, and the use of putti (see for instance the Cavalcanti Annunciation in Santa Croce, Florence or the Brancaccio Tomb in Sant’Angelo a Nilo, Naples, but also, in the Berlin Sculpture Collection: Inv. SKS 3044; Inv. SKS M 7). However, the name of Donatello was never directly pronounced in conjunction with this composition, as the style seems somewhat gentler (and slightly weaker) than that of the master. Soon after its acquisition by the Berlin Museums, Bode 1902 drew attention to similarities with the High Altarpiece of the Ovetari chapel in the church of the Eremitani in Padua (destroyed during WWII), a work attributed since the 16th century by Marcantonio Michiel to a pupil of Donatello, Giovanni da Pisa. Such an attribution was endorsed by Schottmüller 1913 in her first edition of the catalogue of the Berlin Sculpture Collection; but the work disappeared from the second edition (Schottmüller 1933), most probably because the author suspected it to be a forgery (Middeldorf 1938 regretted this omission). The relief was little studied during the Cold War, as it stayed in East Berlin starting in 1958 (it was even declared lost by Sandner 1967; and in European Works of Art… 1990). Recently, Caglioti 2008 reaffirmed its authenticity, reassessing the attribution to Giovanni da Pisa, which he extended to a Virgin and Child bought as a work by Donatello by the Kimbell Museum of Art, Fort Worth in 2006 (see The Borromeo Madonna… 2006, which exaggerates the differences between the two reliefs). The attribution to Giovanni da Pisa of the altarpiece of the Ovetari Chapel has been challenged in a 1994 Ph.D. thesis by Keith Vernon Shaw, who gave to the artist only the left half of the relief, ascribing the other half to the painter Nicolò Pizolo, who is indeed documented as working on the altarpiece. On the basis of this theory, Gentilini 1999 challenged the attribution of the Berlin relief to Giovanni da Pisa: since the closest parallel between the sculpture and the altarpiece is the right half of the latter, he argued, the Berlin relief (ans its related versions) should be given to Pizolo. This attribution was followed by Mozzati 2004; Ortenzi 2006 and in The Borromeo Madonna… 2006. According to Caglioti 2008, the Ovetari altarpiece is coherent in itself and has to be attributed to Giovanni da Pisa, as Pizolo is mainly documented as a painter and could not have achieved a work so closely aware of Tuscan culture after only five years of collaboration with Donatello (Pizolo is documented in the studio of Donatello from 1443, and the Ovetari altarpiece was begun in 1448; he may have only painted the altarpiece after it was modeled). For Caglioti, the numerous references to the art of Donatello in our Madonna may be explained by the participation of the artist to the conception of the work (see also Caglioti 1993). Three other versions of the Berlin relief are known – none of them with the cushion in the foreground (Caglioti 2008, p. 90 suggests that the cushion in the Liechtenstein version may have been removed during an ancient restoration). The composition was also echoed in various paintings produced in Padua in the middle of the 15th century: notably many Virgin and Child by Giorgio Schiavone in the National Gallery, London, in the Galleria Sabauda, Turin, and in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin; the Lichtenstein version of the relief was even tentatively ascribed to Giorgio Schiavone by Magnani 2006. See also Kokole 1990; De Nicolò Salmazo 2006; and Caglioti 2008 for further comparisons, especially with Marco Zoppo. Such a work is in perfect tune with Paduan culture of the mid 15th-century, when the workshops of Donatello and of Francesco Squarcione gave birth to one of the richest productions of the Italian Renaissance, and also saw the emergence of one exceptional artist: Andrea Mantegna (see De Marchi 1996). Literature Bode 1902 Wilhelm Bode, Die italienische Plastik, 3rd edition, Berlin, Georg Reimer, 1902, p. 123: Giovanni da Pisa, the author of the altarpiece of the Ovetari chapel in the church of the Eremitani, Padua. Schottmüller 1913 Frida Schottmüller, Die italienischen und spanischen Bildwerke der Renaissance und des Barocks in Marmor, Ton, Holz und Stuck, Berlin, Georg Reimer, 1913, p. 110 cat. 268: Giovanni da Pisa (in comparison with the altarpiece of the Ovetari chapel in the church of the Eremitani, Padua). Bode 1922 Wilhelm von Bode, Italienische Plastik, 6 ed., 1922, p. 131. (reference to be checked) Planiscig 1927 Leo Planiscig, Andrea Riccio, Vienna, Anton Schroll, 1927, p. 15: Giovanni da Pisa; related to the bronze tondo in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Inv. Pl. 7462 (related to the tondo formerly in Berlin: Inv. SKS M 7). Bettini 1931 Sergio Bettini, “Bartolomeo Bellano ‘ineptus artifex’?”, Rivista d’arte, XIII, 1931, p. 57 fig. 4: Domenico di Paris; reproduces the Liechtenstein version, presented as the Berlin one. Middeldorf 1938 Ulrich Middeldorf, review of Schottmüller 1933, Rivista d’arte, XX, 1938 now in: idem, Raccolta di scritti that is Collected Writings. I. 1924-1938, Florence, SPES, 1979-80, p. 377: does not understand why the sculpture is not in the catalogue of Schottmüller 1933, as it is genuine. Sandner 1967 Oscar Sandner in idem (ed.), Meisterwerke der Plastik aus Privatssammlungen im Bodenseegebiet, exh. cat. (Bregenz, Künstlerhaus Palais Thurn und Taxis, 1 July-30 September 1967), Bregenz, Künstlerhaus Palais Thurn und Taxis, 1967, p. 42: Giovanni da Pisa; John Pope-Hennessy attributed the work to a Paduan follower of Donatello; says that the Berlin version was lost during WWII. European Works of Art… 1990 European Works of Art and Sculpture, London, Sotheby’s, 13 December 1990, p. 24, lot. 34: the Virgin and Child for sale now in the Kimbell Museum, Fort Worth is compared with the present work and with another plaquette in Berlin, see Inv. SKS 3088; lost during WWII (sic). Kokole 1990 Stanko Kokole, “Notes on the Sculptural Sources for Giorgio Schiavone’s ‘Madonna’ in London”, Venezia Arti, 1990/4, p. 52: attributed to Giovanni da Pisa; the angels are reused by Giorgio Schiavone in a Virgin and Child in the National Gallery, London; but also in another work in the Galleria Sabauda, Turin, and in a fresco now in the Musei Civici, Padua. Caglioti 1993 Francesco Caglioti, “Una conferma per Andrea dell’Aquila scultore: la ‘Madonna’ di casa Caffarelli”, Prospettiva, 69, January 1993, p. 24 note 70: the altarpiece of the Eremitani chapel is mostly due to Giovanni da Pisa. De Marchi 1996 Andrea De Marchi, “Centralità di Padova: alcuni esempi di interferenza fra scultura e pittura nell’area adriatica alla metà del Quattrocento”, in Charles Dempsey (ed.), Quattrocento adriatico. Fifteenth-Century Art of the Adriatic Rim, symposium papers (Florence, Villa Spelman, 1994), Bologna, Nuova Alfa Editoriale, 1996, p. 69 note 58: workshop of Pizolo and Giovanni da Pisa. Gentilini 1999 Giancarlo Gentilini, “Intorno alla pala Ovetari: appunti sull’eredità donatelliana a Padova, fra Pizolo e Mantegna”, in Alberta De Nicolò Salmazo (ed.), Francesco Squarcione ‘pictorum gymnasiarcha singularis’, symposium papers (Padua, 10-11 February 1998), Padua, Il Poligrafo, 1999, pp. 199-201 and fig. 164: Nicolò Pizolo, as he is author of the right half of the Ovetari altarpiece (the left half being by Giovanni da Pisa), this theory originates in Keith Vernon Shaw, The Ovetari Chapel: Patronage, Attribution, and Chronology, Ph.D. (University of Pennsylvania, 1994). Banzato 2000 Davide Banzato in idem, Franca Pellegrini and Monica De Vincenti (eds.), Dal Medioevo a Canova. Sculture dei Musei Civici di Padova dal Trecento all’Ottocento, Venice, Marsilio, 2000, p. 110: compared with a lunette with the Virgin and Child in the Musei Civici, Padua (Inv. 198), coming from the church of Santa Lucia and attributed to the workshop of Pietro Lombardo. Darr 2002 Alan P. Darr in idem, Peter Barnet and Antonia Boström, Catalogue of Italian Sculpture in the Detroit Institute of Arts, Volume One. Eighth to Sixteenth Century, London und Turnhout, Harvey Miller Publishers and Detroit Institute of Arts, 2002, I, p. 167: discusses the Detroit version, proven to be ancient through thermoluminescence; the veil and the candelabra are slightly different from the Berlin work. Mozzati 2003 Tomaso Mozzati in Mina Gregori (ed.), In the Light of Apollo. Italian Renaissance and Greece, exh. cat. (Athens, National Gallery, 22 December 2003-31 March 2004), Cinisello Balsamo, Silvana Editoriale, 2003, p. 241: Niccolò Pizzolo; the presence of the cushion signals this is the version closest to the original. Clifford 2004 Timothy Clifford in Peter Humphrey et al. (eds.), The Age of Titian, exh. cat. (Edinburgh, Royal Scottish Academy Building, 5 August-5 December 2004), Edinburgh, National Galleries of Scotland, 2004, p. 350: the attribution to Giovanni da Pisa is “not entirely convincing”. De Nicolò Salmazo 2006 Alberta De Nicolò Salmazo, “Andrea Mantegna e Padova. 1445-1460”, in Davide Banzato, Alberta De Nicolò Salmazo and Anna Maria Spiazzi (eds.), Mantegna e Padova. 1445-1460, exh. cat. (Padua, Musei Civici agli Eremitani, 16 September 2006-14 January 2007), Milan, Skira, 2006, p. 21: attributed to Giovanni da Pisa; dialogue between sculpture and painting. Di Natale 2006 Pietro Di Natale, in Vittorio Sgarbi (ed.), Domenico di Paris e la scultura a Ferrara nel Quattrocento, Milan, Skira, 2006, p. 70: Niccolò Pizolo or Giovanni da Pisa; once attributed to Domenico di Paris by Bettini 1931, which is not impossible. Magnani 2006 Fabrizio Magnani in Davide Banzato, Alberta De Nicolò Salmazo and Anna Maria Spiazzi (eds.), Mantegna e Padova. 1445-1460, exh. cat. (Padua, Musei Civici agli Eremitani, 16 September 2006-14 January 2007), Milan, Skira, 2006, pp. 246-249: the Liechtenstein version is tentatively attributed to Giorgio Schiavone. Ortenzi 2006 Francesco Ortenzi in Vittorio Sgarbi (ed.), La scultura al tempo di Andrea Mantegna tra classicismo e naturalismo, exh. cat. (Mantua, Castello di San Giorgio, 16 September 2006-14 January 2007), Milan, Electa, 2006, p. 68: Niccolò Pizolo. The Borromeo Madonna… 2006 The Borromeo Madonna by Donatello, sale Sotheby’s (New York, 26 January 2006), p. 18: Niccolò Pizolo; insists on the differences with the so-called “Borromeo Madonna” attributed to Donatello now in the Kimbell Museum of Art, Fort Worth. Caglioti 2008 Francesco Caglioti in Giovanni Agosti and Dominique Thiébaut (eds.), Andrea Mantegna, exh. cat. (Paris, Musée du Louvre, 26 September 2008-5 January 2009), Paris, Hazan and Musée du Louvre, 2008, pp. 88-91: Giovanni da Pisa but probably conceived by Donatello, ca. 1450-1455; the Virgin and Child in the Kimbell Museum of Art is also attributed to Giovanni da Pisa. Sbaraglio 2012 Lorenzo Sbaraglio, “Una terracotta di Donatello: la ‘Madonna’ della tomba di Giuliano Davanzati in Santa Trinita”, Nuovi Studi, XVII, n°18, 2012, p. 74: Giovanni da Pisa. Neville Rowley (24 May 2016)

- Location

-

Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

- Collection

-

Skulpturensammlung (SKS)

- Inventory number

-

2949

- Measurements

-

Gewicht: 21,4 kg mit Rahmen

Höhe x Breite x Tiefe: 92,5 x 72,5 x 9,8 cm (mit Rahmen)

- Material/Technique

-

gebrannter Ton, Holz (Rahmen)

- Classification

-

Relief und Rahmen (Sachgruppe)

Skulptur (Sachgruppe)

- Subject (what)

-

Madonna; d.h. Maria mit dem Christuskind

- Event

-

Herstellung

- (who)

-

Giovanni da Pisa, Bildhauer*in

- (where)

-

Padua

- Rights

-

Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

- Last update

- 09.04.2025, 10:14 AM CEST

Data provider

Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst. If you have any questions about the object, please contact the data provider.

Object type

- Skulptur (visuelles Werk)

Associated

- Giovanni da Pisa, Bildhauer*in

![[Madonna mit Kind in einer Nische; The virgin with child in the niche]](https://iiif.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/image/2/cfe7e33c-e165-4896-8180-ee1482e3e226/full/!306,450/0/default.jpg)

![[Madonna mit Kind in einer Nische; The virgin with child in the niche]](https://iiif.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/image/2/262a8a14-1951-424a-9800-81c6d8835c7f/full/!306,450/0/default.jpg)

![[Die Madonna mit dem Kind; The Virgin and Child]](https://iiif.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/image/2/c79627c9-ea2e-46ad-99f0-480ae8ec62ff/full/!306,450/0/default.jpg)