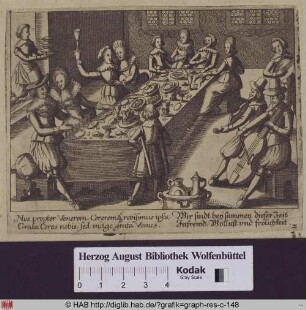

Gemälde

Fröhliche Gesellschaft

In diese heitere, von sinnlichen Genüssen angeregte Gesellschaft wird der Betrachter durch Bewegungen, durch Blicke und durch den Verzicht auf eine Vordergrunddistanz unmittelbar einbezogen. Ein beleibter Alter mit Violine erzeugt eine fast hörbare Ausgelassenheit. Reste einer Mahlzeit, auf dem Boden verstreute Muschelschalen, Weinkannen an der Wand, besonders aber die überaus geckenhafte Kleidung der jungen Herren und ihre provozierende Haltung weisen auf das in der moralisierenden Literatur der Zeit viel gescholtene Luderleben der holländischen Wohlstandsschicht. Das Thema der »fröhlichen Gesellschaft«, wie es im frühen 17. Jahrhundert in der holländischen Malerei verbreitet wurde, hatte stets auch eine belehrende Komponente. Die Komposition Buytewechs besticht durch eine geradezu mathematische Symmetrie. Genau in der Mitte der rückwärtigen Zimmerwand ist ein breitformatiges Landschaftsgemälde – ein Bild im Bilde – aufgehängt. Wie darin drei Baumgruppen am Ufer eines Gewässers aufragen, so gruppieren sich davor sechs Personen paarweise um einen wiederum genau in der Mitte stehenden Tisch. Das Paar hinter diesem dekorativen, die Bildachse betonenden Möbel mit oktogonaler Platte, auf der eine feine Glasschale mit Naschwerk steht, ist dem Betrachter frontal zugewandt. Der Mann blickt ihn zudem aus runden Augen direkt und herausfordernd an, während er mit zärtlicher Geste ein kokett lächelndes Mädchen mit Weinglas an sich zieht. Die beiden seitlichen Figurenpaare wenden sich in Körperhaltung und mit Blicken zwar dem Bildzentrum zu, das ausgestreckte Bein des fast in Schräglage auf dem Stuhle lümmelnden Kavaliers rechts markiert mit dem bis an den unteren Bildrand reichenden Schuh jedoch ostentativ nochmals die Bildachse. Zugleich strebt die jeweils äußere Figur – rechts eine junge Magd mit Zinnschüssel, links ein Kavalier mit großem Federhut – aus dem Raume heraus. In der ursprünglichen Fassung hatte die Zinnschüssel der Magd rechts ihr Äquivalent in einem Tongefäß, in das der Mann links urinierte – den Vorgang schirmte er diskret mit der rechten Hand ab. Einer der Vorbesitzer des Bildes muss dieses Detail als peinlich empfunden haben. Er ließ es so übermalen, dass die gewölbte Hand des Mannes auf einer Stuhllehne ruhte, mit der der unbekannte Restaurator das unziemliche Gefäß einfach übermalt hatte. Eine erhaltene Fotografie des Vorbesitzers gibt den originalen, bei einer späteren Restaurierung wiederhergestellten Zustand wieder. Zugleich zeigt es eine weitere, die Komposition entstellende Übermalung vermutlich des 19. Jahrhunderts. Offenbar erschien dem damaligen Eigentümer das an der Rückwand des Zimmers hängende Landschaftsbild als zu dominant, so dass er es um das rechte Drittel verkleinern ließ. Auch »bereinigte« er den Dielenboden, indem er die dort verstreuten Austernschalen durch Übermalung unsichtbar machte. Diese Art von restauratorischer Willkür an alten Bildern kam häufiger vor. In diesem Fall waren die vermeintlichen Korrekturen bereits vor dem Ankauf des Werks durch die Berliner Gemäldegalerie wieder rückgängig gemacht worden. Noch 1912 konnte Wilhelm von Bode seine intuitive Zuschreibung an Buytewech nicht untermauern, weil Tafelbilder des Malers kaum bekannt waren. Das Berliner Werk aus der Spätzeit wurde daher lange Zeit Dirk Hals zugeschrieben. Buytewech, von Zeitgenossen »de gheestige Willem« genannt, war in der Tat vor allem ein Meister der grafischen Künste. Bis heute sind lediglich acht Gemälde von seiner Hand nachgewiesen.| 200 Meisterwerke der europäischen Malerei - Gemäldegalerie Berlin, 2019 ___________________________________________ Through movements, looks and the absence of distance in the foreground, the viewer is drawn directly into this merry company, animated by sensual pleasures. A corpulent elderly man with a violin generates an exuberance that is almost audible. The remains of a meal, shells scattered on the floor, wine jugs on the wall and above all the dandyish clothing of the young men and their provocative postures point to the dissipated life of the wealthy class in Holland that was often castigated in the moralising literature of the time. The subject of the “merry company”, as propagated in Dutch painting of the early 17th century, always included an element of moral instruction. Buytewech’s composition is notable for its positively mathematical symmetry. A wide-format landscape painting – a picture in the picture – hangs at the exact centre of the back wall of the room. Corresponding to three groups of trees that rise on the banks of a body of water, six persons are grouped in pairs in front of the painting around a table, which in turn stands precisely in the middle. The couple behind this decorative, octagonal-topped piece of furniture, which emphasises the axis of the scene and on which stands a fine glass bowl with snacks, frontally faces the viewer. Moreover, the man directs a challenging gaze through round eyes straight at the beholder, while drawing towards him with a tender gesture a coquettishly smiling girl who holds a wine glass. Through their posture and looks, the two pairs of figures at the side turn to the centre of the picture, but the outstretched leg of the cavalier on the right, who is lolling almost diagonally on the chair, ostentatiously re-emphasises the axis of the painting with a shoe that reaches to the lower edge of the scene. At the same time, the persons on the outside – a young maid with a pewter bowl on the right, a cavalier with a large feathered hat on the left – are making to leave the room. In the original version, the maid’s pewter bowl on the right had a counterpart, an earthenware vessel into which the man on the left was urinating, while discreetly shielding this action with his right hand. A previous owner of the painting must have found this detail embarrassing and had it painted over so that the curved hand of the man rested on the back of a chair, with which the unknown restorer simply overpainted the offending vessel. A surviving photograph belonging to the previous owner shows the original version, which was re-instituted in a later restoration. It also shows a further over-painting, probably dating from the 19th century that disfigured the composition. The landscape painting hanging on the back wall of the room clearly seemed too dominant to the owner at that time, who had it reduced in size by one third on the right. This owner also “cleaned up” the wooden floor, making the oyster shells scattered across the boards invisible through overpainting. This arbitrary way of restoring old paintings was a common occurrence. In this case, the supposed corrections had already been reversed when the work was purchased by the Berlin Gemäldegalerie. In 1912, Wilhelm von Bode was not yet able to provide evidence for his intuitive attribution to Buytewech, as panel paintings by this artist were almost unknown. This late work in Berlin was therefore long attributed to Dirk Hals. Buytewech, called “de gheestige Willem” (witty Willem) by contemporaries, was indeed primarily a master of graphic arts. To this day no more than eight paintings by his hand have been identified. Although Buytewech lived in Haarlem only from 1612 to 1617, the manifold artistic impulses of this city, which was provincial in comparison to Amsterdam, had a lasting influence on him. This work was not painted until later, after the artist returned to his home town of Rotterdam.| 200 Masterpieces of European Painting - Gemäldegalerie Berlin, 2019

- Material/Technique

-

Leinwand

- Measurements

-

Bildmaß: 65 x 81,5 cm

Rahmenaußenmaß: 84 x 102 x 11 cm

- Location

-

Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

- Inventory number

-

1983

- Last update

-

02.05.2023, 11:25 AM CEST

Data provider

Gemäldegalerie. If you have any questions about the object, please contact the data provider.

Object type

- Gemälde

Time of origin

- 1622/1624

![[Fröhliche Gesellschaft; Merry company]](https://iiif.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/image/2/f73312ae-f741-46b2-ba34-f7fe89741cdd/full/!306,450/0/default.jpg)