Gemälde

Der Campo di Rialto

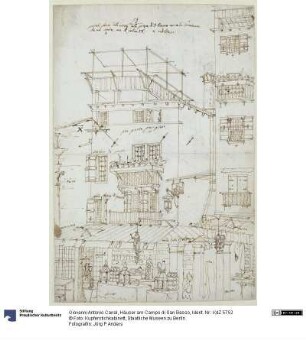

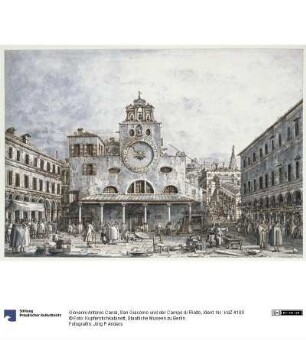

Die Ansicht des Campo di Rialto, des ehemaligen Hauptmarktplatzes und Hauptgeschäftszentrums von Venedig (Sitz der Staatsbank im Portico del Banco Giro), malte Canaletto in seinen letzten Lebensjahren, zwischen 1758 und 1763, nach der Rückkehr aus England, wo er mit kurzen Unterbrechungen von 1746 bis 1755 gewirkt hatte. Das Bild entstand im Auftrag des aus Berlin stammenden, seit Jahrzehnten in Venedig tätigen Kaufmanns Sigismund Streit, zusammen mit einem Gegenstück, einer Ansicht des Canal Grande in Venedig mit dem Palazzo Foscari, dem Wohnsitz Streits, in dem er auch sein Büro hatte. Streit vergab diesen Auftrag im Zusammenhang mit einer großzügigen Schenkung von Kunstwerken, seiner Bibliothek und Barvermögen, die er seiner alten Berliner Schule, dem Gymnasium zum Grauen Kloster, zugedacht hatte. Mit den beiden Bildern wollte er die Stätten seines privaten Lebens und seines beruflichen Wirkens (Campo di Rialto) für die Nachwelt festhalten. Dazu kamen noch zwei Darstellungen venezianischer Volksfeste in Form von Veduten: das Fest der Vigilia di S. Marta bei der Kirche S. Marta, an den Zattere, am Giudeccakanal, und das Fest der Vigilia di S. Pietro bei S. Pietro di Castello; die beiden Bilder haben die gleichen Maße wie die zuvor genannten. Vielleicht sollten sie den Anfang eines Zyklus von venezianischen Festdarstellungen bilden, den Streit dann aber von einem unbekannten Künstler malen ließ, weil er offenbar mit Canalettos Darstellung der Vigilia di S. Marta nicht einverstanden war. Beide Festdarstellungen Canalettos sind Nachtbilder. Sie bilden ein Paar und wirken wie Gegenstücke zu den beiden »Tageslichtbildern«, dem Canal Grande und dem Campo di Rialto. Sigismund Streit (1687-1775) war schon 1709 nach Venedig gekommen und konnte sich 1715 dort als Kaufmann selbständig machen. 1739, mit 52 Jahren, ließ er sich von Amigoni, der gerade aus England zurückgekehrt war, malen und erwarb von ihm insgesamt zehn Bilder mit biblischen und mythologischen Szenen, wohl noch ohne den Gedanken an eine Stiftung. Er war aber nie Kunstsammler im eigentlichen Sinne. 1750 gab er sein Geschäft auf und zog sich zunächst für acht Monate jährlich, seit 1754 dann ganz nach Padua zurück. Er war Junggeselle, und da er sich mit seinem Neffen, der eine Zeitlang bei ihm gearbeitet hatte, überworfen hatte, reifte in ihm der Gedanke, sein Vermögen in eine Stiftung für seine Berliner Schule einzubringen, mit der er seit 1751 deswegen in brieflichem Kontakt stand. Im Hinblick auf die Stiftung ließ er zunächst um 1751/52 von Nogari vier Allegorien mit moralisch-pädagogischen Bezügen malen, die wahrscheinlich für den Bibliothekssaal der Schule bestimmt waren. Nach 1758 folgten die vier Bilder Canalettos, die 1763 nach Berlin versandt wurden. Der Campo di S. Giacomo di Rialto, das Hauptgeschäfts- und Bankenzentrum, lag nicht weit von Streits Wohn- und Geschäftshaus, dem Palazzo Foscari, entfernt, wenn auch auf der anderen Kanalseite. Canaletto hatte in früheren Jahren den Campo di Rialto zweimal in umgekehrter Richtung gemalt, mit Blick auf die Fassade von S. Giacometto (Dresden, Staatl. Kunstsammlungen; Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada), niemals zuvor aber die weniger reizvolle Ansicht mit dem Blick auf die nüchternen Fassaden der von Antonio Abbondi 1520 bis 1522 errichteten Fabbriche Vecchie di Rialto, die den Platz an zwei Seiten begrenzen und Sitz von Handels-, Schiffahrts- und Ernährungsbehörden waren. Die Wahl dieser Ansicht ging offensichtlich auf den Wunsch Streits zurück, der den rückwärtigen Porticato del Banco Giro dargestellt sehen wollte, wo die Staatsgirobank ihren Sitz hatte. Ihre Beamten sitzen an Pulten. Im rückwärtigen Gäßchen sitzen Notare an ihren Schaltern, auch die Versicherungsagenten hatten in der Nähe Büros. Kaufleute gehen im Gespräch auf und ab. Streit erwähnt in seiner Beschreibung besonders die Juden mit ihren roten Mützen und die Armenier in langen Gewändern und spitzen Hüten. Am mittleren Pfeiler des Porticato sieht man den »gobbo di Rialto«, eine von Pietro da Salò 1541 geschaffene Skulptur, über deren Rücken eine kleine Treppe auf die »Colonna del bando« führt, von der ein »comandador« Verlautbarungen verlas. Fremden Kaufleuten wurde erlaubt, sich hier zu versammeln. Links im Bild erscheint die »Ruga degli orefici«, benannt nach den Goldschmieden, die im Sottoportico ihre Läden hatten, im Hintergrund der Campanile von S. Giovanni Elemosinario. Vor den Läden sieht man Verkaufsstände mit Fleisch, Gemüse, Obst und Keramik. Im Vordergrund und am rechten Porticato werden Haushaltswaren, Möbel, Gemälde und andere Kunstgegenstände angeboten. Die weitwinklige Perspektive läßt den Platz sehr viel größer und monumentaler erscheinen, als er in Wirklichkeit ist. Die Pflasterung mit dem mäanderartigen weißen Muster, wie es noch heute besteht, scheint im Jahre 1758 vorgenommen worden zu sein, womit ein Terminus post quem für Canalettos Bild gegeben ist. Die Monumentalität des Raumes, die kühle trockene Klarheit der Atmosphäre, die penible Exaktheit in der Wiedergabe der Architektur, die kalligraphische Pinselschrift, die Farbigkeit mit der Bevorzugung von sandigen Beiges, Brauns und rötlichen Tönen und die Vorliebe für das genrehafte Ausspinnen der Details sind Charakteristika für Canalettos Spätstil.| 200 Meisterwerke der europäischen Malerei - Gemäldegalerie Berlin, 2019__________________________________________Canaletto created this view of the Campo di Rialto, the former main market square and commercial centre of Venice (with the seat of the state-owned bank located in the Portico del Banco Giro), in his final years, between 1758 and 1763, and following his return from England, where he had worked with brief interruptions from 1746 until 1755. The painting was executed on a commission from the merchant Sigismund Streit, a native of Berlin, who had been active in Venice for several decades, together with a pendant, a view of the Canal Grande in Venice with the Palazzo Foscari, Streit’s residence, where he also maintained his office. Streit awarded the commission in conjunction with a generous donation of artworks, his library, and monetary assets intended for his old Berlin school, the “Gymnasium zum Grauen Kloster”. Through these two pictures, he wanted to preserve the places of his private life and professional activity (Campo di Rialto) for posterity. There were also two depictions of Venetian folk festivals in the form of vedute: the Festival of Vigilia di Santa Marta at the Church of Santa Marta on the Zattere on the Giudecca Canal, and the Festival of Vigilia di San Pietro at San Pietro di Castello; both have the same dimensions as the above-mentioned works. Perhaps they were intended as the inception of the cycle of depictions of Venetian festivals which Streit, however, had painted instead by the young Antonio Diziani, evidently unsatisfied with Canaletto’s depiction of the Vigilia di Santa Marta. Both of Canaletto’s festival scenes are night pictures. They form a pair, and function as counterparts to the two “daylight pictures”, the Canal Grande and the Campo di Rialto.Sigismund Streit (1687–1775) arrived in Venice in 1709, becoming an independent merchant in 1715. In 1739, when he was 52, he had himself portrayed by Amigoni, who had just returned from England, acquiring altogether ten pictures from Amigoni depicting biblical or mythological scenes, probably still without any thought of an endowment. He was however never an art collector in the genuine sense. In 1750, he gave up his business and moved to Padua, initially for eight months annually, then permanently in 1754. He was a bachelor, and having fallen out with his nephew, who had worked for him for a time, he began to develop the idea of converting his estate into an endowment for his Berlin school, with which he maintained a correspondence beginning in 1751. It was with an eye toward this endowment that he began by having Nogari execute four allegories conveying moral and pedagogical messages in 1751/52, probably intended for the school’s library hall. Following in 1758 were the four pictures by Canaletto, which were sent to Berlin in 1763. The Campo di San Giacomo di Rialto, the main commercial and banking centre, was not far distant from Streit’s residence and business premises, albeit on the opposite side of the canal. In earlier years, Canaletto had depicted the Campo di Rialto twice from the opposite direction, with a view of the façade of San Giacometto (Dresden, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen; Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada), but had never painted the less attractive view with the sober façades of the Fabbriche Vecchie di Rialto, erected by Antonio Abbondi in 1520–22, which delimits the square on two sides, and served as the headquarters of the agencies responsible for commerce, shipping, and foodstuffs. Evidently, the choice of this view is attributable to the wishes of Streit, who wanted to see a depiction of the rearward Porticato del Banco Giro, where the state clearing bank had its headquarters. The banks officials are seen seated at desks. Seated at their counters in the rearward alley are notaries, and insurance agents had offices nearby. Merchants walk back and forth, engaged in conversation. In his description, Streit mentioned in particular the Jews, with their red caps, and the Armenians, attired in long robes with pointed hats. Visible alongside the central pillar of the Porticato is the Gobbo di Rialto (Hunchback of the Rialto), a sculpture created by Pietro da Salò in 1541, whose back supports a small staircase on the Colonna del bando, from which a “comandador” would read proclamations. Foreign merchants were allowed to assemble here. Visible on the left is the Ruga degli orefici, named for the goldsmiths who had their shops in the sottoportico, and in the background, the campanile of San Giovanni Elemosinario. Seen in front of the shops are the stalls where meat, vegetables, fruit, and ceramics were sold. Offered in the foreground and in the right-hand side porticato were household goods, furniture, paintings, and other art objects. The wide-angle perspective allows the square to seem far larger and more monumental than it actually is. The paving, with its meandering white pattern, which still exists today, seems to have been undertaken in the year 1758, thereby providing a terminus post quem for Canaletto’s picture. The monumentality of the space, the cool, dry clarity of the atmosphere, the meticulous precision of the architectural rendering, the calligraphic brushwork, the colour scheme, with its preference for sandy beige, brown, and reddish tones, and the fondness for the genre-style elaboration of details are all characteristics of Canaletto’s late style.| 200 Masterpieces of European Painting - Gemäldegalerie Berlin, 2019

- Standort

-

Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, BerlinDeutschland, BerlinDeutschland

- Inventarnummer

-

Streit.5

- Maße

-

Rahmenaußenmaß: 196 x 129,5 x 7 cm

Bildmaß: 119,3 x 186,6 cm

- Material/Technik

-

Leinwand

- Ereignis

-

Eigentumswechsel

- (Beschreibung)

-

Seit 1964 Leihgabe der Streitschen Stiftung, Berlin

- Ereignis

-

Herstellung

- (wer)

- (wo)

-

Italien

- (wann)

-

ca. 1758 - 1759

- Letzte Aktualisierung

- 09.04.2025, 10:13 MESZ

Datenpartner

Gemäldegalerie. Bei Fragen zum Objekt wenden Sie sich bitte an den Datenpartner.

Objekttyp

- Gemälde

Beteiligte

Entstanden

- ca. 1758 - 1759

![Imaginary view of S. Giacomo di Rialto [Fingierte Ansicht von San Giacomo di Rialto]](https://iiif.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/image/2/8d072040-133c-4a14-8ef3-2088da96f752/full/!306,450/0/default.jpg)